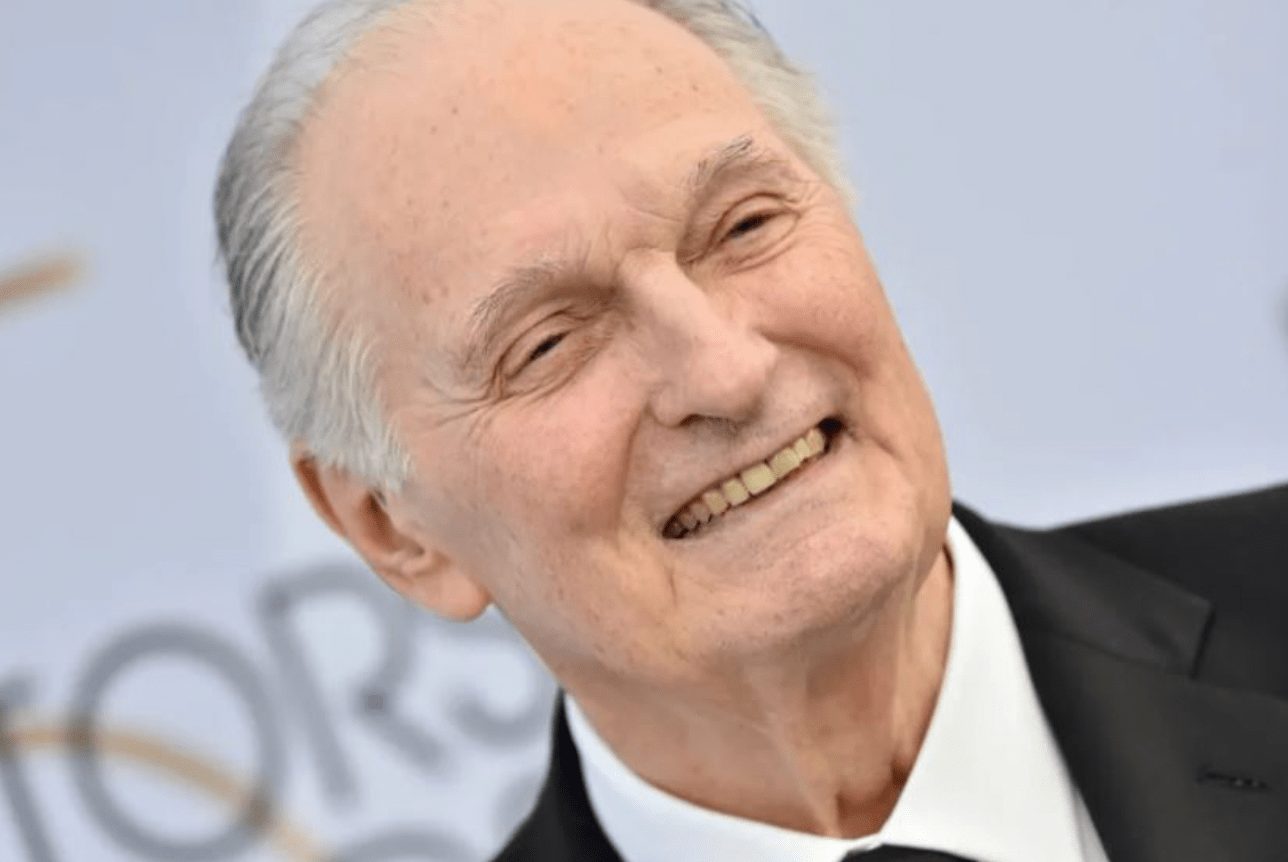

At the age of 86, Alan Alda, best known for his portrayal of a military doctor in the classic dramatic sitcom MASH, has solidified his position as an industry veteran.

But in 2018, the adored actor revealed to the world that he had received a Parkinson’s disease diagnosis three years earlier, and that the ailment had now become a part of his life.

Alda courageously discusses the most difficult aspect of having this ailment and how it has changed his outlook on life while relentlessly pursuing his objectives.

Let’s continue to explore his views to learn more about the significant challenge he faces with Parkinson’s disease and the steps he takes to slow its progression.

Alda’s adventure began when he experienced an unexpected symptom, which prompted him to contact a doctor. In 2015, he was given a Parkinson’s disease diagnosis.

The turning point occurred when Alda read an article in The New York Times by a team of medical professionals describing an unusual Parkinson’s disease indication known as REM sleep behavior disorder, in which people physically act out their dreams while they are still asleep.

Alda had an incident with AARP Magazine in 2020 after reflecting on this realization: “I realized I had done just that. In my dream, I attacked the person I thought was attacking me by throwing a sack of potatoes at him. A pillow was thrown at my wife.

Alda was convinced that he could have Parkinson’s disease, and he insisted on having a brain scan despite the doctor’s suggestion against it because he had no normal symptoms.

To his surprise, the doctor called to confirm the actor’s suspicions: “Wow, you got it,” the doctor said.

Alda claimed that since his illness, this realization has been his greatest burden.

Alda emphasizes that he has lead a full life since learning he has Parkinson’s, despite struggling with the realities of the disease. During the pandemic’s quarantine period, he continued to perform, started a well-liked podcast, and relished the extra family time that was given to him.

When asked by People what she found to be the most difficult part of having Parkinson’s, Alda modestly shared a relatively minor issue: “Tying shoelaces can be difficult with stiff fingers. He pondered the idea of playing the violin while sporting mittens.

Alda choose to negotiate his particular circumstances with serenity rather than giving in to the pressure of optimism or despair. Being positive or negative about everything is meaningless. We only have uncertainty, so you have to learn to surf it, he told AARP.

The silver lining, he continued, “is that I’m becoming more confident that I’ll always be able to find a solution.” Alda is adamant that life is a journey that is continuously changing and reinventing itself.

Alda asserts in his unshakeable attitude that it might be possible to slow the growth of his Parkinson’s condition. Seven years after his diagnosis, Alda said that he is healthy and doing well.

He cheerfully declared, “I’m feeling great and moving forward.” He actively uses all available tools to slow the progression of Parkinson’s disease, which can in fact be controlled with effort.

Alda follows a daily schedule that includes physical treatment appointments, a variety of exercises, podcast preparation, chasing geese off his lawn, playing chess with his wife Arlene, and binge-watching Scandinavian TV shows.

Alda walks, bikes, and even practices boxing under the supervision of a Parkinson’s therapy expert, adhering to a thorough training plan specifically adapted to his condition because he understands the value of exercise for his long-term health. Through these attempts, he aims to keep his motor skills and overall physical health.

I frequently dance to music. I learn how to box from a man who has had Parkinson’s treatment. I perform a full-body workout designed specifically for this condition.

It’s not the end of the world if you get this diagnosis. Alda wants people to understand that receiving a Parkinson’s diagnosis does not mean one’s life is over.

Alda wants to change how people view Parkinson’s disease by being open about his health.

He told the Wall Street Journal, “One of the reasons I talk about it in public is to remove some of the stigmas because I know people who have just been diagnosed who feel like their lives are gone, and they’re stunned and upset.

He agrees that it is typical for people to experience depression after hearing such news, but Alda emphasizes that it is not necessary. He emphasizes that although circumstances may surely be worse, a Parkinson’s diagnosis does not spell the end of life.

“You die from it, not with it,” Alda has a positive attitude and whenever she can, laughs for comfort. “Laugh! Laughter is healthy. One of the biggest benefits of this pandemic isolation is that. I’m laughing like I’ve never laughed before with my wife.

You reveal yourself when you laugh. You’re becoming more vulnerable. You’re not secure. But there are so many advantages to being vulnerable. He said, “Even now, we can’t take ourselves too seriously. You let the other person in, which draws us all closer.”