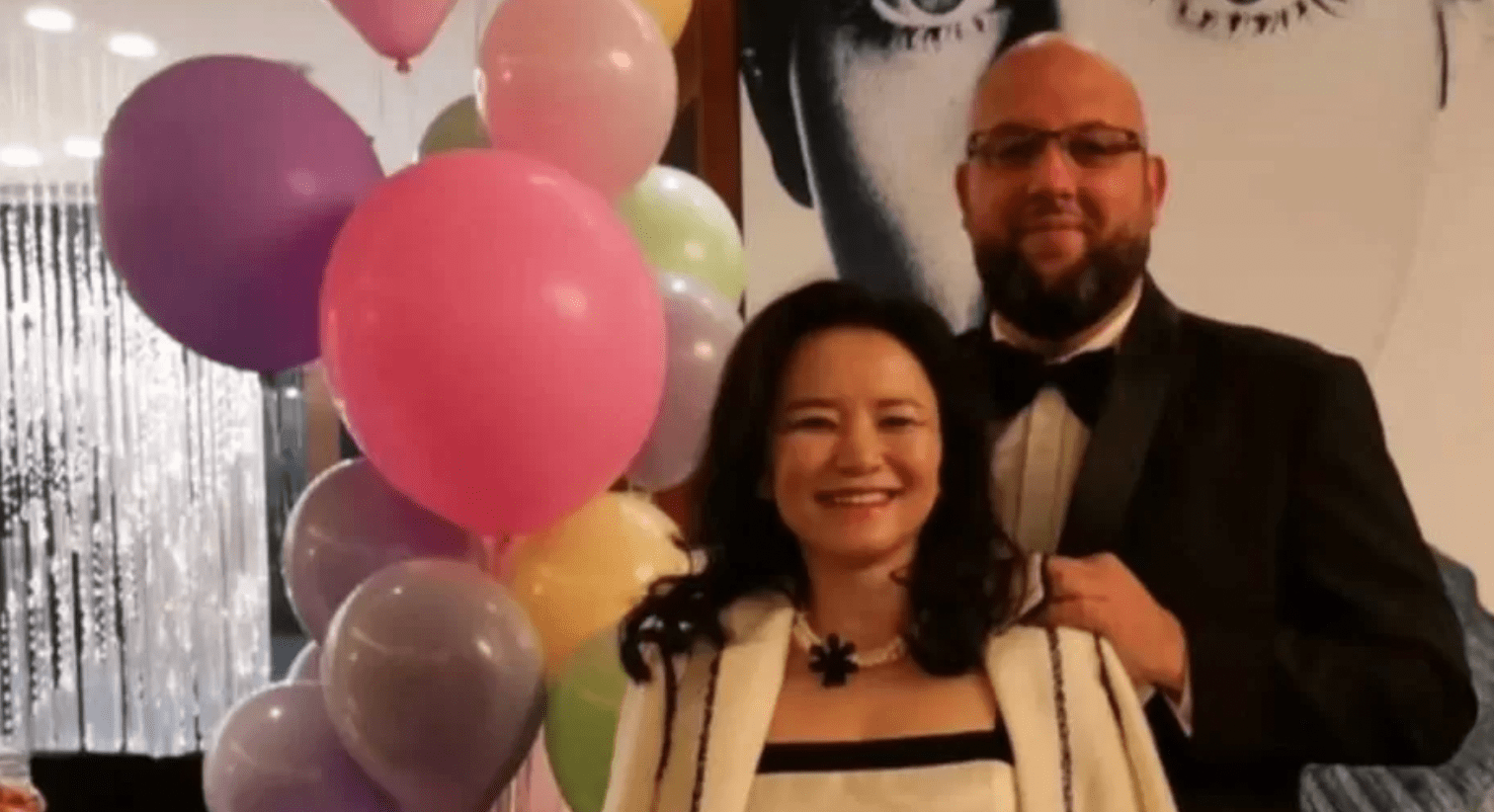

Nick Coyle, the partner of Australian journalist Cheng Lei, describes her 1,000 days of imprisonment in a Chinese prison as a shockingly lengthy period. The charges against her remain undisclosed, and she has not yet received a sentence. Along with other friends and family of Cheng, Coyle expresses confusion about what she is accused of and why she is being subjected to this treatment. He urges the relevant authorities in China to bring a swift resolution to this distressing situation.

Cheng Lei was employed as a business reporter at China’s state-run English language television station, CGTN when state security officers apprehended her on August 13, 2020, and subsequently accused her of “illegally supplying state secrets overseas.” She was subjected to six months of solitary confinement, stress positions, and interrogations without access to legal representation. She has since been held with other prisoners.

In March of last year, Cheng’s trial took place behind closed doors, with even Australia’s Ambassador to China, Graham Fletcher, being denied entry. However, her sentencing has been repeatedly delayed.

Nick Coyle, the former chief executive of the China-Australia Chamber of Commerce, has now left Beijing but continues to advocate for Cheng’s release from overseas. Despite China’s ambassador to Australia, Xiao Qian, expressing hope for a speedy resolution in January, Coyle laments that they are still waiting five months later.

Yang Hengjun, another Australian citizen charged with state secrets violations, has also experienced repeated sentencing delays. In China, the definition of what constitutes a “state secret” is broad and flexible, leaving it open to interpretation by the government. Detaining foreigners for extended periods under an opaque, party-controlled legal system is proving to be a challenge for a country trying to attract international business investment, especially in the wake of strict COVID-19 lockdown measures.

The detention of Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, who were released hours after the US extradition request against Huawei’s chief financial officer Meng Wanzhou was dropped, was seen as an act of hostage diplomacy. Nevertheless, foreign companies still face pressure. Just six weeks ago, a Japanese executive from a pharmaceutical company was detained on suspicion of carrying out espionage activities, and international corporate research firms have also been raided in recent weeks.

As a result, potential foreign investors are evaluating the risks of doing business in China while also considering the obvious appeal of the country’s vast domestic market.

Australia and China have experienced significant tensions in recent years, with Beijing imposing sanctions on Australian exports, including wine, barley, and lobsters. In Australia, where more than 5% of the population has Chinese ancestry, these tensions have been particularly challenging.

Despite the different treatment of foreign passport holders with Chinese ancestry in detention compared to other foreigners, Cheng Lei’s case has attracted significant attention. The fact that her children have not been able to see her since her arrest, when they were nine and 11 years old, has struck a chord in Australia and beyond.

Nick Coyle notes that “fair-minded Australians – from business to political leaders and in the general public – do not accept the status quo.” However, China’s foreign ministry has attempted to downplay global concerns surrounding the case, stating that “China’s judicial authorities have handled the case in accordance with the law, fully protecting Cheng Lei’s legal rights.”

Despite this, there has been no judgement more than a year after her secret trial, despite promises that one would be passed “in due course.”

The conviction rate in China is nearly 100%, which means that being charged with an offense in China almost certainly leads to a guilty verdict. Under these circumstances, lawyers and supporters do what they can to minimize the punishment that the accused might face. When it comes to foreigners, their governments attempt to negotiate with their Chinese counterparts to secure the release of their citizens, which can sometimes involve deals.

The Chinese government is keen on seeing a visit to Beijing by Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese later this year to formalize a recent thaw in relations. The cases of Cheng Lei and Yang Hengjun could be used as bargaining chips by the Australian side to clear the path for this visit to take place. The Australian government has raised their cases on many occasions.

During a recent television interview while in London for the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, Mr. Albanese said that “our position on China has been to engage constructively but to continue to put forward that the impediments to trade should be removed, to say very directly to President Xi, that Australians such as Cheng Lei need to be given proper justice, and that they’re not receiving.” It is worth noting that Mr. Albanese mentioned President Xi Jinping by name. Beijing is unlikely to have missed this detail.

It is a heartbreaking situation for Cheng Lei and her family. The pain of separation must be immense, and it is clear from her messages that she is desperate to be reunited with her children. Her case is just one example of the challenges faced by individuals caught up in political tensions between nations, and the toll it can take on families and loved ones. As efforts continue to secure her release, many will be hoping for a positive outcome that can bring an end to this difficult chapter and allow Cheng Lei to return home to her children.