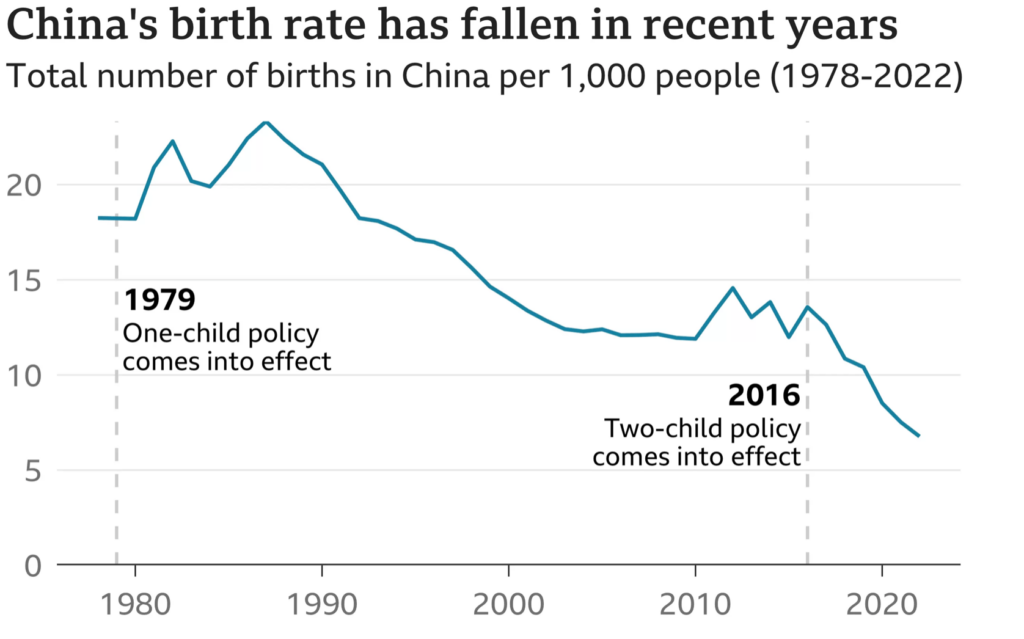

The declining birth rates pose a significant challenge for several prominent economies in Asia. Governments in the region have allocated substantial financial resources, amounting to hundreds of billions of dollars, in an attempt to reverse this trend.

Japan initiated policies to encourage couples to have more children in the 1990s, followed by South Korea in the 2000s. Singapore implemented its first fertility policy as early as 1987. More recently, China, which experienced its first population decline in 60 years, has also joined this group of countries taking measures to address the issue.

The cost of these policies is challenging to precisely quantify, but South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol revealed that his country had spent over $200 billion (£160 billion) in the past 16 years to stimulate population growth. However, despite these efforts, South Korea set a new record for the world’s lowest fertility rate last year, with an average of only 0.78 babies expected per woman.

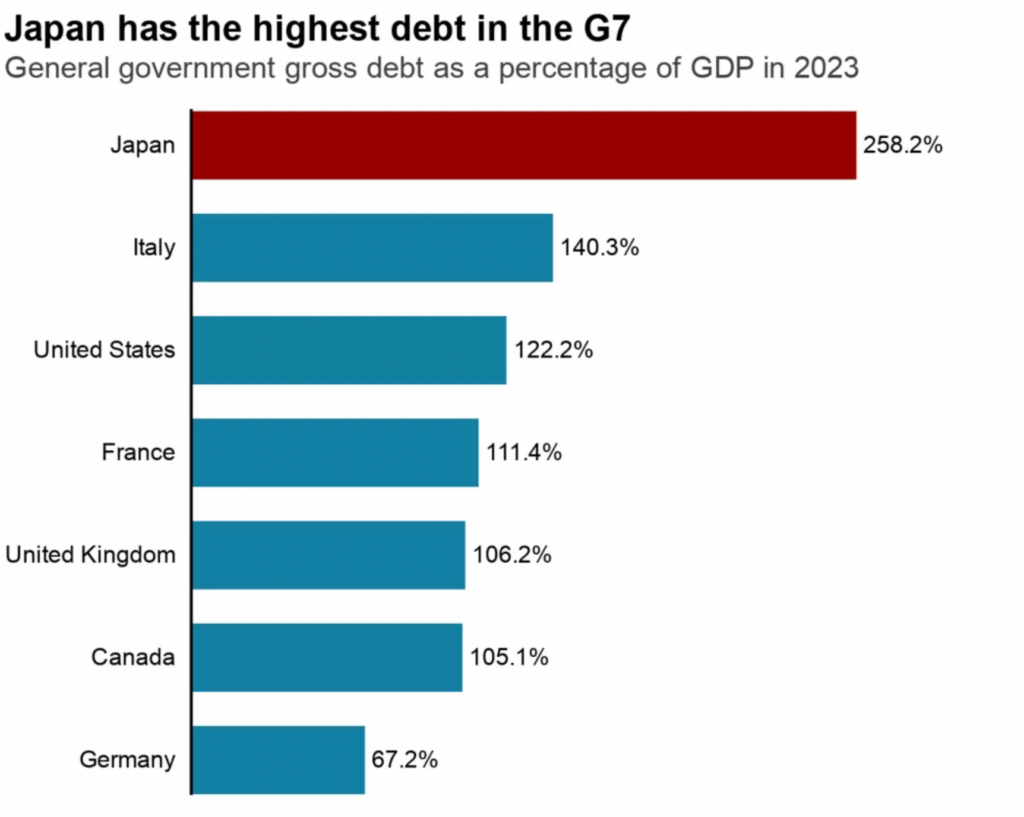

In neighboring Japan, which also experienced a record low number of births at fewer than 800,000 last year, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has committed to doubling the budget for child-related policies to 10 trillion yen ($74.7 billion; £59.2 billion), which accounts for just over 2% of the country’s gross domestic product.

On a global scale, the United Nations’ most recent report indicates that while there is an increasing number of countries aiming to reduce birth rates, the number of nations seeking to raise fertility rates has more than tripled since 1976.

Governments in these countries seek to grow their populations primarily due to economic considerations. A larger population can contribute to increased productivity and the production of goods and services, ultimately leading to higher economic growth. While a larger population may entail higher costs for governments, it can also result in greater tax revenues.

Furthermore, many Asian countries are facing rapid population aging. Japan, for instance, has nearly 30% of its population over the age of 65, and other nations in the region are not far behind. This demographic shift places a strain on the economy as the proportion of the working-age population decreases, while the cost and responsibility of caring for the non-working population, particularly the elderly, increase.

In contrast, countries like India, which recently surpassed China as the world’s most populous nation, have a significant advantage in terms of demographics. With over a quarter of its population aged between 10 and 20, India possesses substantial potential for economic growth.

However, nations with negative population growth coupled with an aging population face challenges in sustaining support for the elderly. As Xiujian Peng from Victoria University pointed out, such trends can have adverse effects on the economy and the ability to provide adequate support for the elderly.

The effectiveness of measures implemented to increase birth rates in Asia has been limited, according to data from Japan, South Korea, and Singapore over the past few decades. Various strategies such as financial incentives for new parents, subsidized or free education, additional nurseries, tax benefits, and extended parental leave have been employed. However, the Japanese finance ministry conducted a study that deemed these policies unsuccessful, a sentiment shared by the United Nations.

Alanna Armitage from the United Nations Population Fund stated that historical evidence shows that attempts to incentivize women to have more children, known as demographic engineering, have not yielded significant results.

She emphasized the importance of understanding the underlying factors preventing women from having children, often related to the challenges of balancing work and family life. The high cost of raising children and gender inequality were also mentioned as significant factors.

In contrast, Scandinavian countries have experienced better outcomes with fertility policies compared to Asian nations, as highlighted by Xiujian Peng. This success is attributed to their robust welfare systems, lower costs associated with raising children, and more balanced gender equality.

Asian countries have ranked lower in the global gender gap report published by the World Economic Forum, further underscoring the challenges they face in this regard.

Funding the expensive measures to address low birth rates, particularly in Japan as the world’s most indebted developed economy, raises significant concerns. Japan is considering options such as selling more government bonds, which would increase its debt, or raising the sales tax or social insurance premiums. However, these options come with drawbacks. Increasing debt burdens future generations, while raising taxes or insurance premiums could further strain already struggling workers, potentially discouraging them from having more children.

Antonio Fatás, an economics professor at INSEAD, argues that regardless of the effectiveness of these policies, investment is necessary. While fertility rates may not have increased significantly, reducing support could potentially result in even lower rates.

Governments in the region are also investing in other areas to address the challenges posed by shrinking populations. China, for instance, is focusing on technology and innovation to compensate for the declining labor force and mitigate the negative impacts of a shrinking population, as highlighted by Ms. Peng.

Additionally, although unpopular in countries like Japan and South Korea, discussions are taking place regarding potential changes to immigration rules to attract younger workers from overseas. As Ms. Peng mentioned, with declining fertility rates globally, there is a competitive race to attract young people to come and work in different countries.

Overall, despite the uncertainties surrounding the effectiveness of fertility policies, these governments seem to have little choice but to invest in them. The financial implications and alternatives are challenging, and addressing the issue is crucial for the future of their economies.